One of the key points of Jungian dream interpretation is that most dreams are compensatory. To compensate comes from the Latin word compensare which means to equalize and balance.

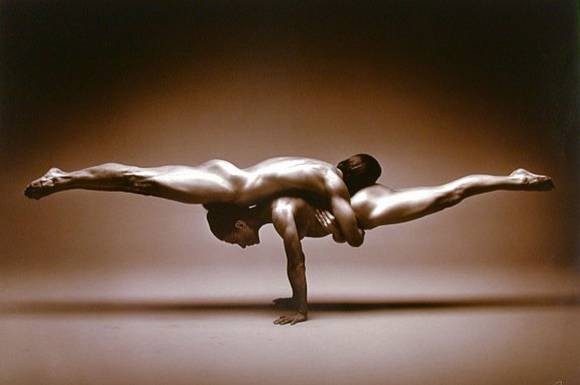

Balance

www.drkin.com

Equalization and balance require an objective comparison of different viewpoints and elements in order to produce a needed correction. In other words, the dream serves as a counterweight when consciousness becomes too concentrated, limited, one-sided, or arbitrary.

A dream can also be complementary, that is to say, it adds what is missing to contents that are too narrow or underestimated in consciousness.

Compensation or complementarity occur because the psyche seeks equilibrium between its conscious and unconscious parts. A dream reorganizes the psychic economy in the present so as to be able to face current challenges. A dream knows that tomorrow depends on what we are and do today.

In Jungian psychology the ultimate function of the dream is to provide a better knowledge of ourselves by reaching the inner core and truth of our being. The dream leads to knowledge of who we really are and what corresponds or not to our true nature. Dreaming challenges us to question ourselves and to move forward.

Certain dreams are not compensatory or complementary; they do not affect the dreamer’s psychic balance and do not require any change in consciousness. Premonitory and telepathic dreams are two examples.

Dreams can play a determining role in an individual’s destiny, and even in the destiny of an entire civilization.

- Dreams bring solutions to intellectual or mathematical problems as shown by Descartes and the scientist Niels Bohr who discovered in a dream the atomic model that bears his name.

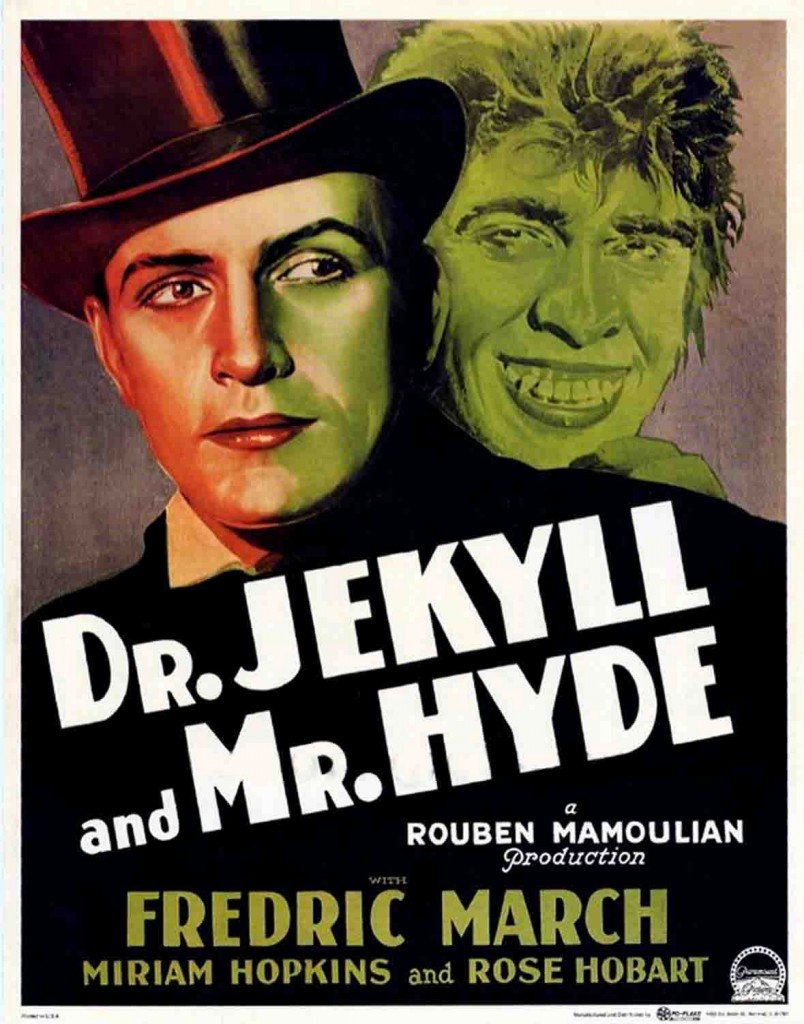

- Dreams inspire poets, painters, writers, and musicians who often are far ahead of their time. In one of his dreams, Robert Louis Stevenson found the plot for his masterpiece “Doctor Jekyll and Mr. Hyde.”

hollywoodclassic.hautetfort.com